|

DAY 2 I started out the second day of construction on this long knife by concentrating on the handle. I knew this design was going to be a bit different from my previous battle knives (see my gallery).

The first step was to take my knife to the kitchen table, lay it on top of the hard stock paper that I use for my patterns, and carefully trace around the entire knife outline. I then cut out this paper outline and, using a pencil, tried out different designs for the handle. My main design concern was to make this handle look a bit different than most Terran blade handles. In addition,I had to make sure I left at least one inch of steel near the butt end of the handle exposed so some of the steel would show through, as seen in the artwork where this knife is shown.

Once I had a good design drawn, I cut out the handle and marked on it where I wished the brass pins to go. Then I punched small holes through the paper at the pin locations, placed the paper on top of the steel of the knife, and used a magic marker to dab ink into the holes, leaving marks on the blade to locate where to drill the holes.

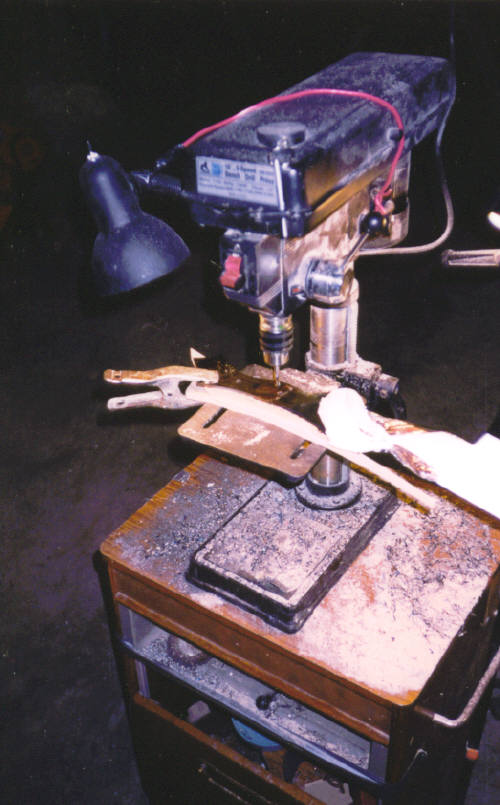

It's now time to bundle up and head out ot the forge where I used my drill press to drill holes where the magic marker marks indicated.

Next I took my paper pattern, placed it on the wood for the handles and traced around it. I did this a second time, one for each side (always make sure that the pattern of both wood sides are marked so that the same side is aways up).

When you cut out the oak handle slabs, you always leave a little extra wood on the sides to be sanded down later. However, on the ends (i.e., the parts that border the knife blade) you trim this very close. Then take the handle to the sander and place bevels on the ends. This is done because you will not be able to sand this part of the handle later without scratching the finish on the blade.

The next step is coloring the steel. Now, I don't really have any photographs of the actual process because it was surprising how little time it took to color the steel on this particular weapon. For more information on how I color-treat the steel, please refer to "The Color of the DaQo'tah Blade", webpage on this site. I colored the steel with a torch until I achieved remarkably dark blue to dark violet colors.

Gluing the handle on comes next. There are several steps. First I glue on one of the oak slabs into position on the knife handle. I use JB Quik Weld, a type of epoxy with an extremely short setting time (around six to eight minutes). Once the first handle's slab glue is set, I use the drill press to drill the holes for the pins. To do this, I simply set the weapon with the one oak slab pointed down and drill through the holes in the steel. I like to have a piece of scrap wood under the oak handle to prvent the drill bit from tearing the wood as it emerges.

I then glue the remaining oak handle on, take it to the drill press (again, flipping the blade so the undrilled piece of oak is on the underside) and drill from the top through the previously drilled holes, so I end up with precise holes.

The next thing is to place the brass pins into the handle to help stablize it. To make brass pins, I cut a section of 1/4 inch thick brass rod to about a half-inch longer length than the thickness of my glued handle. I take the brass pins to the belt sander where I slightly bevel a point on the end of each pin. This point will help ease the pin into the oak wood which sometimes can be rather snug. I then take both pins, lay them on a sheet of sand paper and then use my electric palm sander and sand the pins for a few seconds. This is to scratch the pin's surface slightly so it will cling to the epoxy better. I mix up some JB Quik using a paper plate and plastic spoon, drip a bit of the epoxy into the pre-drilled holes in the knife handle, then roll the brass pin in the epoxy before placing it, pointy end down, into the hole in the handle.

Then I carefully tap the pin down into place, making sure that about a quarter-inch or so pops out the other side. After the pins are set, I have found that the brass pins sand down extremely easily with the belt sander.

Continue sanding on the weapon, starting with the coarser sandpapers, until the handle feels comfortable in your hands. I like to start with an extremely aggressive 60 grit sandpaper to take off the bulk of the sharp corners, then switch to 120 on my electric sander, then finally finishing with some of that auto-body black sandpaper.

Staining the weapon handle is easy and fun, but you must remember to take steps to keep your blade's finish protected. I tape my blade as best I can with masking tape and try not to use too much stain (to avoid drips onto the blade). I have read in some knife magazines that the next step is to lightly sand the weapon and stain it again. I have yet to try that method, but it does intrigue me. After the stain is good and dry, apply a protective coat of whatever lacquer or polyurethane you wish. Again, you can sand the handle after this step if you want.

Because my weapons are so darkly colored, it has proven to be very challenging to display them properly. Lighting a weapon such as this requires a little imagination, as well as the placement in the room to do the most justice to your weapon.

I've chosen to display this particular weapon at the foot of the stairs, for there it seems to dominate the eye of my guest as they enter into my rec room.

Please let me know if you have any questions about the production of this weapon. There is a spot on my website where you can contact me, or simply e-mail me at daqotah@hotmail.com.

|